My grandfather is gone.

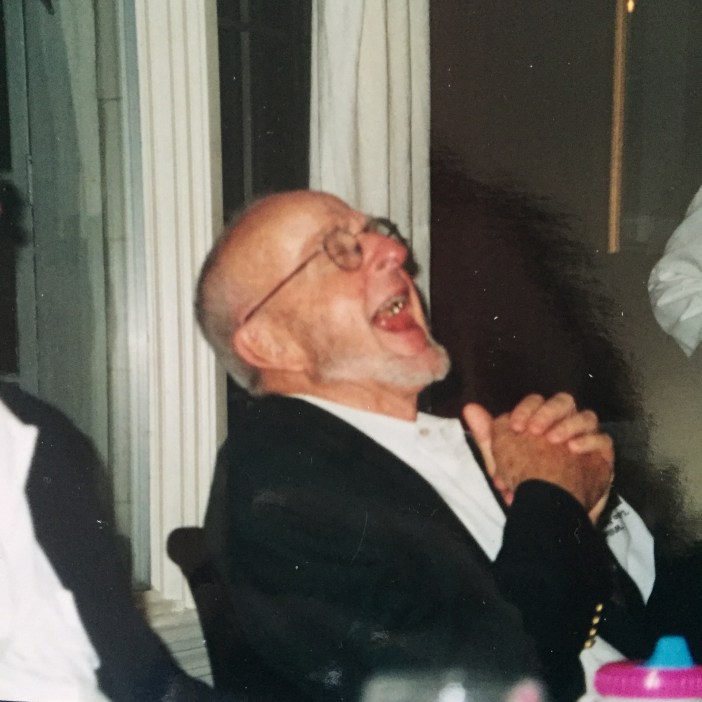

This weekend marked the first time I have ever been to Boston and not seen him. The entire city feels amiss. Everything is gray, and all the buttons are in the wrong buttonholes. And since thirty-two years of being greeted on trips back east with a signature Jim Broderick “Ho-ho!” don’t come to a close without some kind of emotional undoing, I’m all choked up and writing this on an airplane.

I’m a crier by nature, but these tears are the kind that I’m not comfortable letting go of. Letting go of these tears just facilitates letting go of my grandfather, and at this point, I’d rather make a burning nest of them in the back of my throat than let them fall.

Dramatic, perhaps, but I can be a dramatic person. I think he enjoyed that about me.

People have been asking me since his passing last month, “Were you close?” It’s a well-meaning question, but it’s also unanswerable. Far is not the opposite of close, I realize, but all I can think to say is, “We were close and we were far.”

My younger brother, Sam, and I grew up in California. My parents are both Bostonians and the oldest of five, and our nuclear family is the only contingent on either side to have made a home outside of New England. Consequently, my grandfather was not a part of my day-to-day existence; he wasn’t someone I ever expected to be at my recitals or school plays (although he and my grandmother did fly out to watch me ham it up as Mame in Auntie Mame when I was in 10th grade), and I never spent a Christmas with him.

But Sam and I did spend every June counting down the days until we would fly to Boston for the summer’s end. We could never sleep the night before a flight to back east, and we would squeal with excitement when the Super Shuttle pulled up to our house in the darkness of 5 a.m. to ferry us to the airport.

My friends would brag about their upcoming family vacations to places like Disneyworld and the San Diego Wild Animal Park, and I just remember smiling and feeling sorry for them. This was partly because my mother was (and remains) exceptionally vocal about the repulsiveness of popular, commercial vacation destinations, but mostly because I knew that Disneyworld couldn’t possibly hold a candle to what we had in New England. And so much of what we had was about Grandpa and his brilliant, hilarious clan of Brodericks.

I loved going back east because I felt special there. Special, wanted, and important. As far back as I can remember, my grandfather—a genius by virtue of his Harvard graduate degree alone in my eyes—seemed genuinely interested what I had to say. He loved dissecting people’s motivations and internal processes. Even as a child, I knew that Grandpa was interested in my experience of the world and that he took me seriously. And I was definitely a little girl who wanted to be taken seriously.

I never had to hustle for my worth with him or prove that my opinions and experiences were worthy of serious consideration; this was a given. As an adult, I’m still trying to figure out what real intimacy actually means, but I’m pretty sure it has something to do with being seen—really and truly seen. Being seen by others is fundamentally all we want as human beings, and Grandpa always made me feel seen. If the speeches at his memorial this weekend were any indication, he made everyone feel this way.

So where do we go from here? What does my grandmother do when she wakes up each morning to an empty space in the bed next to her? How do I accept that the absence I feel isn’t just the result of allowing too much time to lapse between visits, but rather the result of a final, permanent shift?

I have no answers. This is all new to me. Death in the family is, for the most part, new to me—I’m lucky this way. I suppose I should spend some time being grateful that I still have three more grandparents who are alive and kicking…or at least pantomiming some version of kicking. I am grateful for this. I really am. But still, nothing about this feels okay. We are now in after. It’s uncomfortable. Unacceptable.

I’m terrible with endings, conclusions, goodbyes, partings, closing arguments, and letting go as a general practice (ask anyone), so I think I’ll end by saying thank you.

Thank you for making me feel like the most interesting person in the entire world every single time we spoke. Thank you for teaching me to appreciate a well thought-out garden and Eames chairs. Thank you for the childhood games of Keep Away and the force-feedings of classical music. Thank you for telling Grandma that you were struck by how beautiful I grew up to be after our visit last spring. She told me. I cried. Thank you for all of it. To borrow from your own words to my father just before you left us, I’ve enjoyed it all.

We all have.

I love you.

***