I used to write poems.

I always thought it was dumb to write poems.

I still think this.

I should probably write poems again.

* * *

Purple.

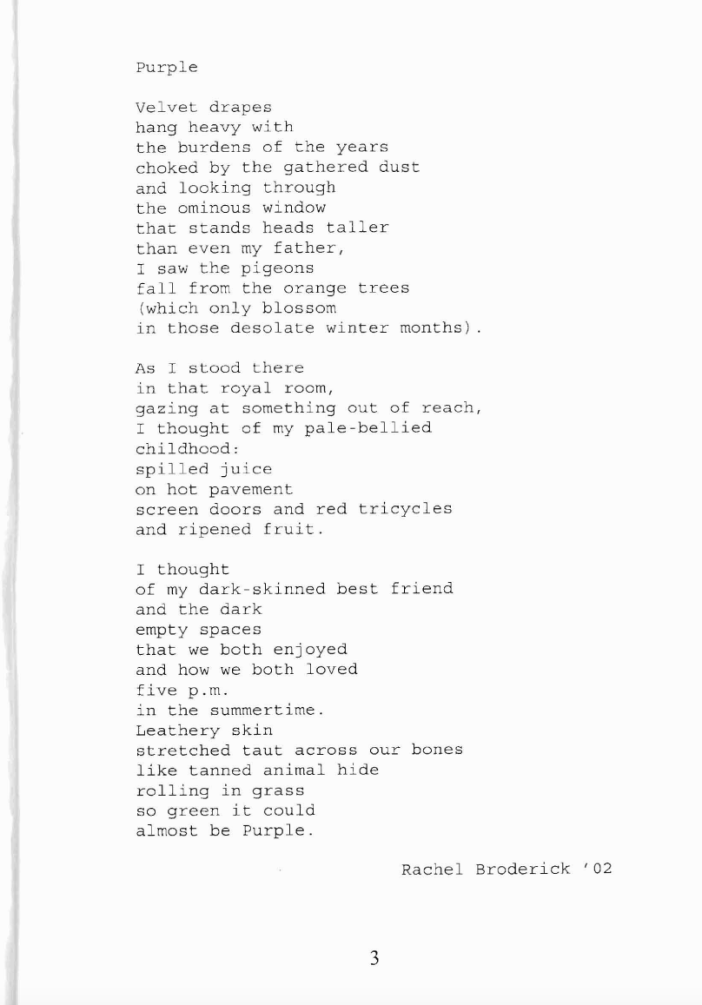

For almost a decade, I have been searching for a copy of a particular poem I wrote when I was fourteen. I hadn’t been able to remember if it was actually any good or not, but I remembered everything else about it and around it. I have been piecing together lost moments of lost years lately, and somehow, finding this poem became critical. An obsession.

I remember writing it. It still feels so recent and familiar—sitting in the Main Hall computer lab at my all-girls school, eating shitty vanilla-cream sandwich cookies from the snack machine while furiously typing every line that danced out of my achey little heart. It was a soul dictation. An angsty, adolescent soul dictation written during the last twenty minutes of a lunch period and due to be placed in Judy Chu’s hot little hands by the end of the day.

Ms. Chu was my 9th grade English teacher. She loved my writing. I loved her for loving my writing.

* * *

Jump cut to 10th grade. Now I’m sixteen. I’m sixteen, and I’m wearing my skin inside-out. I’m so raw and exposed that a passing breeze can light my nerves on fire. I feel everything, and all of it hurts. I don’t show up when I’m supposed to, and I rarely turn in my homework. Because I fucking can’t.

Instead, I’m drinking and smoking and using and bingeing and starving and crying. Crying, crying, crying. All the time. The Big Feelings had established their roots in my limbic system years ago (7th grade? 8th grade? hard to say), and by 10th grade, they had swallowed me whole.

So when my final poem is due in Ms. Lipschutz’s creative writing class, I dig through my archives. Because at this point, if I do turn in my homework, you’re either getting copied answers or recycled assignments from brighter days gone by. Sorry, but what do you want from me? I’M ON FIRE. This is the best I can do.

I find the poem. The 9th-grade-Main-Hall-computer-lab poem. “Purple,” I had titled it. I have no memory of that title or of the poem, but I turn it in and pass it off as new material. And Ms. Lipschutz likes it. Her sweet, rubbery face lights up when she reads it aloud a second time for the class. What a strange lady, I think. I fall asleep on my desk.

The school year ends, I am stuffed to the gills with SSRIs, and I hate myself more than ever. I am not sober. I attend all of the end-of-year ceremonies that seem to be de rigueur at girls’ schools. There is always a piano processional and polite clapping at these ceremonies. And I always smile and polite-clap for as long as I can, or until I’m swept away by the undertow of my own, ever-present shame and taken elsewhere.

Shame has always done that to me. My heart races, the abusive thoughts get louder and more intrusive, and then, without warning, all frequencies turn to static, drowning out everything around me and lulling me into a fantasy world.

I’m at one of these end-of-year ceremonies, watching all of the shiny pennies collect their awards and accolades. The deafening, internal refrain of, ‘You are a total fuck-up; you will never be happy,’ is about to reach fever pitch and give way to the static. I can feel it. But I am jolted back into the moment by the Head of School calling Rachel Abelson to the stage to present the latest edition of Outlook, the annual student-run literary journal.

Rachel Abelson is a class-of-2000 senior, the co-editor of Outlook, and the best writer I have ever known in real life. She is tall and complicated. She has enviously large breasts and unapologetically cold, blue eyes. She wears Doc Martins and vintage sweaters with our required school uniform pants. (We are also allowed to wear uniform skirts, but Rachel always wears pants.) Her hair is often messy. She barely speaks, and when she does, she speaks with purpose. Most importantly, Rachel Abelson is exactly who I want to be.

Rachel’s writing is so sharp and nuanced and original that it makes me sick with jealousy. Once, in a poem, she described her vagina as “that Saturn sunset just below my dust-bunny navel” or something like that. I’m sorry, but what 17-year-old comes up with shit that good? It’s not even fair.

She has probably already had sex, I thought when I heard that line for the first time. She is just too fucking good.

Anyhow, Rachel takes the stage, thanks the Head of School, and coyly tells the audience that she and the Outlook staff believe that the new millennium is going to mark an incredible epoch in modern literature.

“As evidenced by the works produced by the young writers in Ms. Lipschutz’s classes this year,” Rachel declares, “the literary world should brace itself for something exciting and incredible.”

A lofty claim, I think to myself.

She continues, “To give you an idea of what we all have to look forward to, the editors of Outlook would like to read one of our favorite submissions this year, written by an extraordinarily gifted and talented member of the class of 2002. This is ‘Purple’ by Rachel Broderick.”

And with that, Rachel Abelson reads my poem. What. The. Fuck. Rachel Abelson—who I worship and who has never spoken a single word to me—reads my poem.

Everyone claps.

My parents are in the audience somewhere.

Maybe they are all just polite-clapping. I don’t know, and I don’t care. Because for the rest of that afternoon and pieces of the days following, I do not hate myself.

* * *